Mobile Menu

- About Us

- Research

- Education

- Policy & Data

- News

- Resources

- Giving

Ontario’s Rolling Meadow Dairy has launched a line of milk this fall from cows that eat mainly grass. This new alternative — which is a better choice for consumers concerned about fat — is informed by the work of a University of Toronto researcher.

Grass-fed dairy has about the same amount of fat as conventional milk, which mostly comes from cows that eat corn and grains. But the type of fat in grass-fed milk is vastly different. Its ratio of omega-6s (which promote inflammation) to omega-3s (which are anti-inflammatory), for example, is about 3:1. Standard milk comes in about 10:1.

“It’s amazing to see what diet can do to an animal’s nutritional profile,” says Richard Bazinet, who holds the Canada Research Chair in Brain Lipid Metabolism in the Department of Nutritional Sciences. Bazinet tested Rolling Meadow’s product in the year before its launch — free of charge — and found the omega numbers ranged from 2:1 during the summer grazing months to 3.5:1 in winter, when the cows ate stored grass and oats.

Bazinet ran their product through a gas chromatographer, which let him isolate more than 40 fats and verify the omega numbers. “Sales have been excellent, and Richard’s research has been a big catalyst for our launch,” says Rolling Meadow’s CEO, Matthew von Teichman.

There are more than 400 types of fat in milk and researchers are just beginning to piece together how they react with each other — and with other foods — to affect the body and brain. But most nutritionists agree that the omega-6 to omega-3 ratio is a good marker for a healthy fat balance in food, and that it should be around 5:1 or lower.

The omega ratio in the average Western diet today is about five times higher than that of people a century ago. Nutritionists attribute this change to our consumption of animals that eat grains and corn on industrial farms, and our use of vegetable oils like safflower and sunflower, which are high in omega-6s.

Bazinet has tested beef, poultry, and pork from about a dozen small farms in Southern Ontario, where the cows eat grass, the chickens forage for plants and insects, and the pigs eat everything — including soil. The omega ratios were consistently three to five times better than food from industrial farms.

“The nice thing about eating food from these small farms is that you get more omega-3s and fewer omega-6s,” says Bazinet, who is also a researcher in the Centre for Child Nutrition & Health. “Omega-3s limit inflammation, help cells communicate, and can reduce the risk of heart disease and dementia. Omega-6s are important for health, but they tend to increase inflammation.”

Omega-6s can limit the benefits of omega-3s, Bazinet says, because the two compete for the same enzymes as our cells metabolize fats. Simply increasing your omega-3 intake by consuming products fortified with them, such as some conventional milk and juice, may not be a good approach.

Bazinet, who does most of the cooking for his family, says food from small farms also tastes great — with a few exceptions. “The best and worst steaks I’ve had were grass-fed. There are variables, including soil, sunshine, and grass type. But flavour is Mother Nature’s way of attracting us to nutrients,” he says.

The connection between a food’s flavour, its nutritional profile, and how it was produced can be critical for small farmers when they market their food. Mark Schatzker, a food writer whose upcoming book The Dorito Effect explores the potential of flavour as a guide for healthy food choices, has introduced Bazinet to several farmers and food producers.

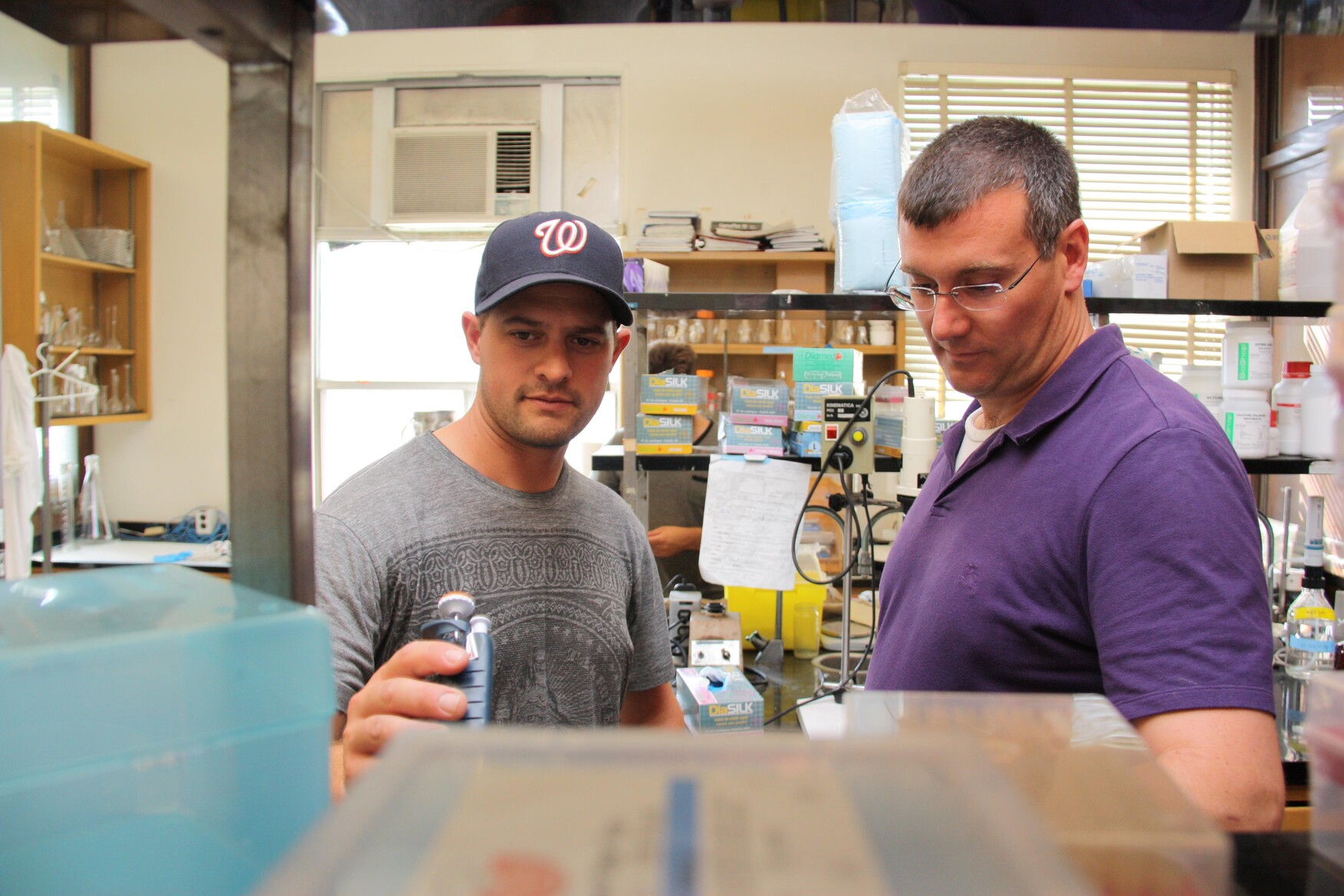

Schatzker recently put Bazinet in touch with Blackview Farm’s Bill Parke, who raises heritage animals with organic methods like pasture rotation and natural fertilizers. Parke sells a lot of his product to chefs in high-end restaurants, where the emphasis is often on flavour. Bazinet recently found Parke’s beef, chicken, and pork has outstanding omega ratios, and Parke now cites the health benefits of his food as well.

“There was always the idea that this kind of food is better for you, but I didn't understand it and had no proof that it was, so I didn't promote it. Now, with positive test results, I can reassure buyers about the nutritional value of their purchase,” says Parke.

This summer Parke supplied chef Tyler Shedden with Tamworth pork, a breed of slow-growing pig that likes to forage, for an event at Café Boulud. Parke and Bazinet say there was a moment of silence when people tried the pork belly. “We’re giving chefs some different flavours to work with, and the hope is that customers will say, ‘This is delicious, and I feel great about eating it too,’” says Parke.

Bazinet hopes more chefs will notice that the most flavourful dishes are often the most nutritious and that more small farmers will trumpet the health benefits of their food. “If this catches on a bit more at the grassroots level, maybe people won’t be faced with 30 feet of frozen pizzas when they enter the supermarket,” he says.

Photo: Bill Parke and Richard Bazinet (by Jim Oldfield)