Breadcrumbs

- Home

- Policy & Data

- Advancing Public Policy

- Not Enough Food on the Table

Not Enough Food on the Table

1 in 8 Households Face this Public Health Crisis

Overview

“There’s nothing to eat!” — that familiar lament at the fridge door is more about mood than food for most middle-class families. Yet for a shocking number of Canadians, it’s a genuine challenge.

Household food insecurity is defined as a lack of adequate food, or secure access to food, due to financial constraints. That can include worrying about running out of food, having lower quality and quantities of food, reducing intake, missing meals and even going days without food.

Prof. Valerie Tarasuk, of the Department of Nutritional Sciences at the University of Toronto, says the scale of the issue in Canada is alarming. The number of Canadian children under 18 living in food insecure homes — 1.15 million — is more than the population of Halifax, Saskatoon and Victoria combined.

Through almost 25 years of ongoing research, Prof. Tarasuk has meticulously examined the impact of this insecurity on Canadian children and families. She has also identified practical solutions that can make a real impact. “The power of public policy is so clear,” she says.

Through her research program, called PROOF, she and her colleagues have raised the profile of food insecurity, and of what’s needed for progress. Here’s what they revealed and what we can do about it to improve the health of children and others.

What’s the scope of the problem?

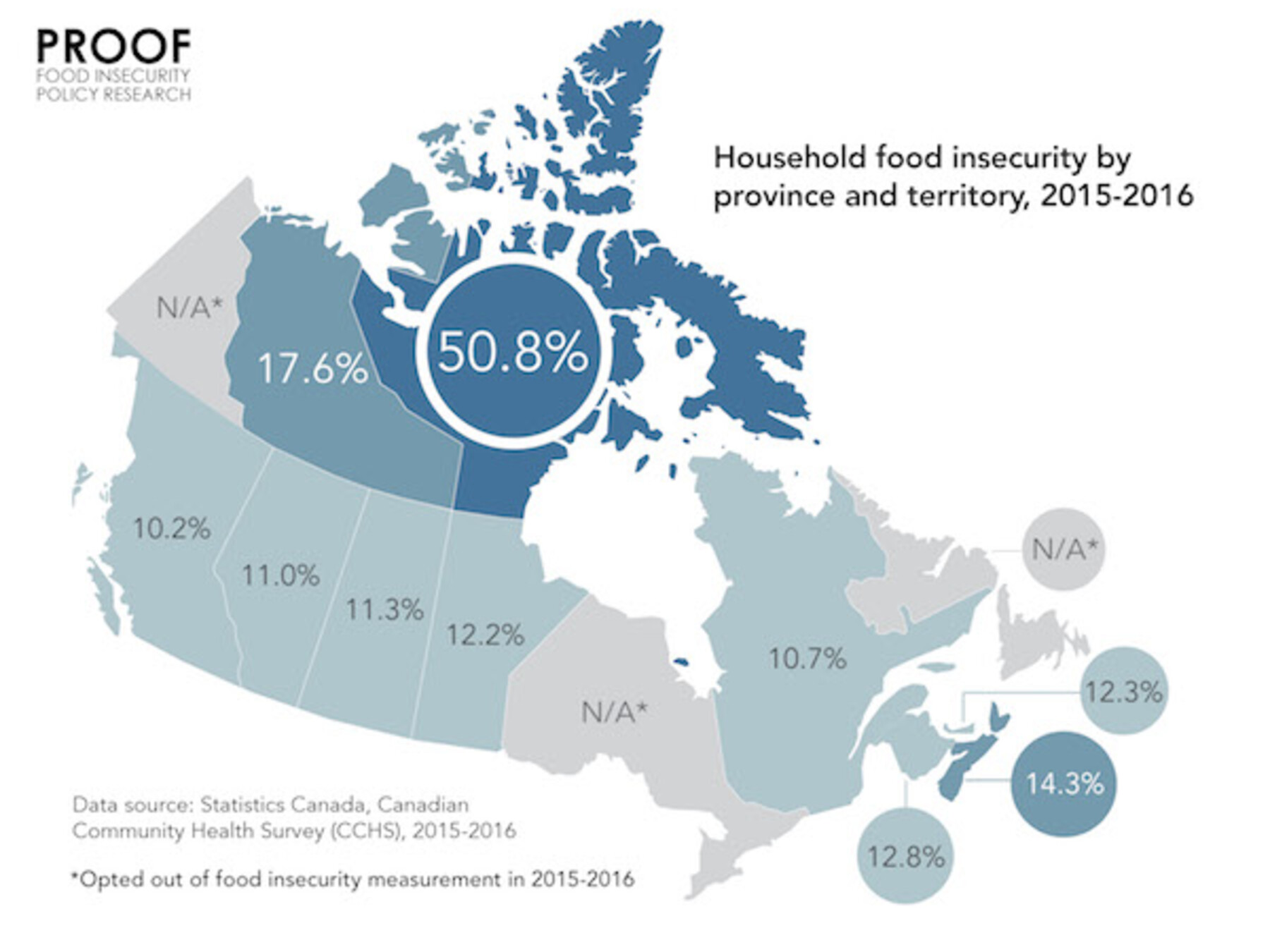

Household food insecurity affects about 4 million Canadians. That’s 1 in 8 households that struggle to consistently put enough food on the table.

What are U of T researchers learning?

Food insecurity is a massive public health problem, often much larger in scale than Canadian citizens and elected representatives imagine, and one that negatively affects physical, mental and social health.

Prof. Tarasuk is part of U of T’s Lawson Centre for Child Nutrition. Her team applied novel interpretive methods to population survey data to generate comprehensive statistics on the magnitude of food insecurity. They charted trends, and detailed the socio-demographic characteristics of those affected. The research uncovered a terrible toll:

- Food insecurity leaves people vulnerable to a wide range of chronic conditions (hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, bowel disorders, stomach or intestinal ulcers, back problems, arthritis, asthma, and more).

- Exposure to food insecurity leaves an indelible mark on children, with greater risks of mental health issues (depression, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, etc.) now and later in life.

- And this shortens lives. In one study of Ontario adults (mean age: 51.3), (1) people in a severely food insecure household had more than double the chances of dying in the next four years compared to someone who is food secure.

That’s the staggering human cost. Then there are the subsequent health-care costs. Another study (2) showed that, compared with food-secure adults, expenditures on health care were 16% higher for adults with marginal food insecurity, 32% higher for adults with moderate food security, and 76% higher for adults with severe food insecurity. That includes everything from physician services, to hospital care, to home care.

Prof. Tarasuk also found that adults from food insecure households made up almost 40% of the adults hospitalized for mental health reasons in Ontario. (3)

Along with this work, Prof. Tarasuk points to a series of studies on the results of federal and provincial policy interventions on the prevalence and severity of food insecurity.

She says the most important of these studies examined the protective effects of old-age pensions on food insecurity among low-income adults; (4) and the impact of Newfoundland and Labrador’s poverty reduction strategy. (5) In both cases, there was a big reduction in food insecurity rates.

How is the Lawson Centre advancing understanding from the lab to society?

Taken together, this work has shed new light on household food insecurity as a potent social determinant of health in Canada, and on the forces that can reduce this problem.

Along with publishing research in influential scientific journals, Prof. Tarasuk works to get the message out to stakeholder groups through:

• Online reports and fact sheets; (6)

• Presentations to policy-makers such as the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology; and

• Talks at major public health group and NGO conferences including Food Secure Canada, Dietitians of Canada, Community Food Centres Canada, and Closing the Gap — Action for Health Equity, which drew over 6,000 views on YouTube.

With the scale of the problem, do food banks actually help? Not as much as you might think.

While food banks remain the primary public response to food insecurity in Canada, Prof. Tarasuk and colleagues showed that they serve only a small fraction of the population in need, and don’t necessarily provide enough nutrition to those they serve.

“I wouldn’t even say it’s a solution,” says Prof. Tarasuk. People get the illusion that that problem is being managed. Meanwhile, she says, food banks don’t address root causes. That highlights the need for more effective responses.

What can be done to make a difference?

Social assistance in itself doesn’t necessarily solve the problem. In fact, social assistance recipients are more likely than not to be food insecure. That suggests that these programs are not designed in ways that enable people to meet their basic food needs.

In Newfoundland and Labrador, food insecurity among social assistance recipients dropped by almost half from 2007 - 2012 after the province rolled out a new poverty reduction strategy. It tackled the depth of poverty through interventions like increasing income support rates and indexing rates to inflation. The results are evidence that food insecurity among social assistance recipients can be reduced by improving their benefits.

The relatively low rate of food insecurity among Canadian seniors also reflects the protection afforded by the guaranteed annual income they receive. Only about 7% of households reliant on seniors’ pensions or retirement incomes report some level of food insecurity.

Prof. Tarasuk says the most meaningful move that governments can make around food insecurity is to ensure adequate incomes. “I would like to see every income transfer program have a goal of enabling households to be food secure,” she says. That includes, for instance, the Canada Child Benefit.

She’s optimistic about the August 2018 federal poverty reduction strategy, which talks about food insecurity. Naming it as part of the problem (under the pillar of dignity and basic needs) at least puts Canada in a position to address this issue through income-related tools. “That’s the most hopeful thing I’ve seen in years on this issue,” says Prof. Tarasuk.

How can concerned citizens get engaged?

Advocacy efforts need to focus on a major overhaul of social assistance programs in Canada. Almost 70% of households reliant on social assistance are food insecure. That indicates that social assistance benefits do not actually cover the costs of basic needs.

As Prof. Tarasuk notes, we also need policies to address the high vulnerability of people in the workforce. Almost two-thirds of food insecure households rely on employment incomes. Tackling their vulnerability means tackling the growing problem of low-waged, part-time, short-term, precarious work. One group that’s advocating for change is Food Secure Canada; see foodsecurecanada.org to learn how to get your voice heard on federal consultations.

Prof. Valerie Tarasuk is part of the Joannah & Brian Lawson Centre for Child Nutrition, a network of researchers and educators affiliated with the University of Toronto. Together, they’re working to improve child health and prevent obesity, malnutrition and chronic disease. Three departments in the Faculty of Medicine — Nutritional Sciences, Family & Community Medicine, and Paediatrics — lead the Lawson Centre. The goal is healthier children living longer through better nutrition, in Canada and around the world.

References

- “Food insecurity status and mortality among adults in Ontario, Canada”; Gunderson, Tarasuk, Cheng, de Oliveira and Kurdyak; PLOS ONE, Aug. 2018.

- “Association between household food insecurity and annual health care costs”; Tarasuk, Cheng, de Oliveira, Dachner, Gunderson and Kurdyak; CMAJ, Aug. 2015.

- “The relation between food insecurity and mental health care service utilization in Ontario””; Tarasuk, Cheng, Gunderson, de Oliveira and Kurdyak; Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 63, 2018.

- “Reduction of food insecurity among low-income Canadian seniors as a likely impact of a guaranteed annual income”; McIntyre, Dutton, Kwok and Emery; Canadian Public Policy, Sept. 2016.

- “An exploration of the unprecedented decline in the prevalence of household food insecurity in Newfoundland and Labrador, 2007-2012”; Loopstra, Dachner and Tarasuk; Canadian Public Policy, Sept. 2015.

- Food Insecurity Policy Research, https://proof.utoronto.ca.