Mobile Menu

- About Us

- Research

- Education

- Policy & Data

- News

- Resources

- Giving

Researchers at the University of Toronto have found that food industry interactions with government heavily outnumbered non-industry interactions on Bill S-228, also known as the Child Health Protection Act, which died in the Senate of Canada in 2019.

The researchers looked at more than 3,800 interactions, which included meetings, correspondence and lobbying, in the three years before the bill failed. They found that over 80 per cent were by industry, compared to public health or not-for-profit organizations.

They also found that industry accounted for over 80 per cent of interactions with the highest-ranking government offices, including elected parliamentarians and their staff and unelected civil servants.

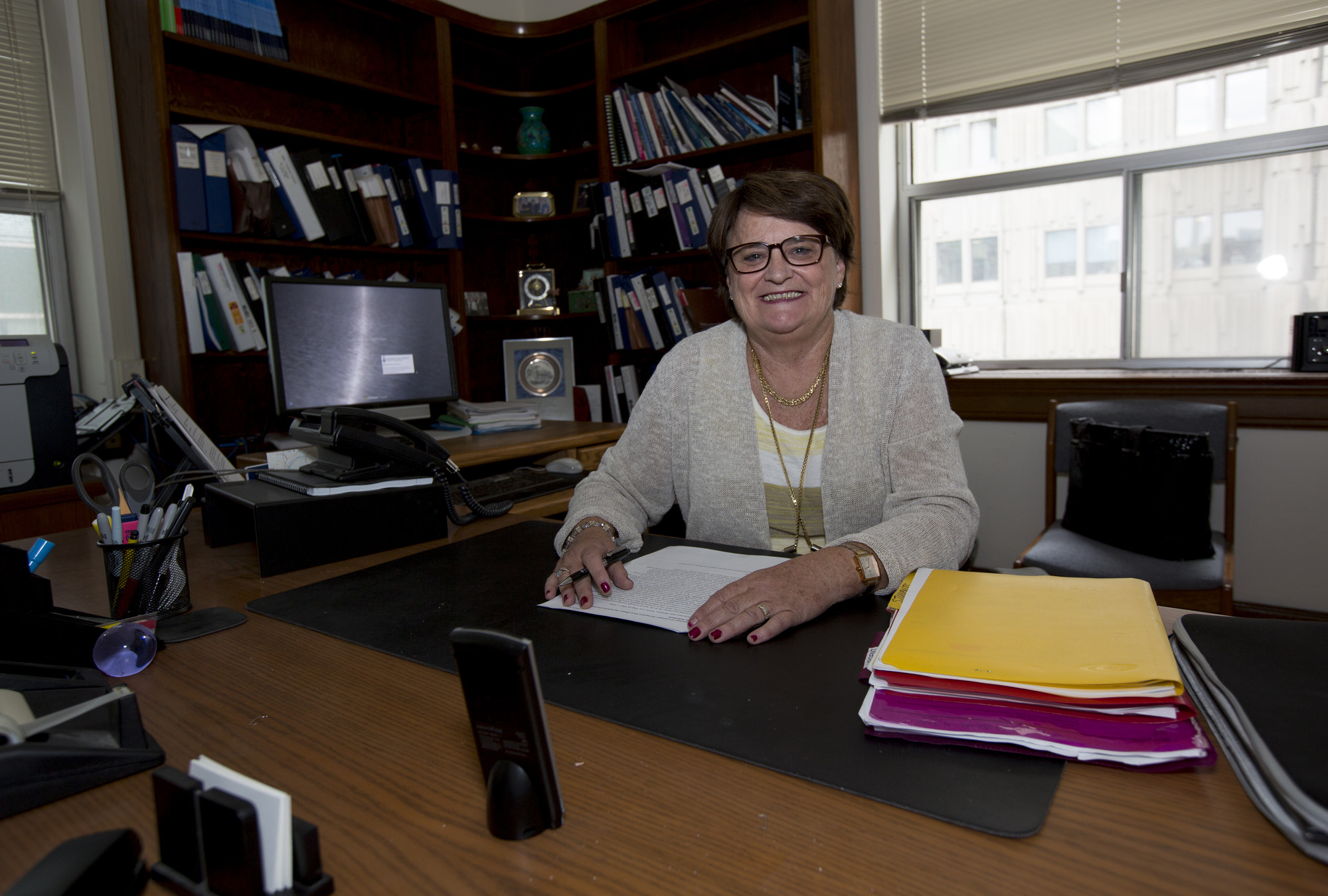

“Industry interacted with government much more often, more broadly, and with higher ranking offices than non-industry representatives in discussions of children’s marketing and Bill S-228,” said principal investigator Mary L’Abbé, a professor in nutritional sciencesand the Joannah & Brian Lawson Centre for Child Nutrition at U of T's Temerty Faculty of Medicine.

The journal CMAJ Open published the studytoday.

The researchers drew data from Health Canada’s Meetings and Correspondence on Healthy Eatingdatabase, set up in 2016, which details the type and content of interactions between stakeholders and Health Canada on nutrition policies. They also used Canada’s Registry of Lobbyists, which tracks the names and registrations of paid lobbyists but provides limited details on the content of the meetings.

“We’re fortunate to have access to this information in Canada, as it offers insight into the story of government bills,” said Christine Mulligan, a doctoral student in L’Abbé’s lab and lead author on the study. “Industry stakeholders bring important viewpoints, but the volume and breadth of their lobbying on this bill was clearly disproportionate, especially compared to public health.”

“We’re fortunate to have access to this information in Canada, as it offers insight into the story of government bills,” said Christine Mulligan, a doctoral student in L’Abbé’s lab and lead author on the study. “Industry stakeholders bring important viewpoints, but the volume and breadth of their lobbying on this bill was clearly disproportionate, especially compared to public health.”

The food industry has a long history of effective lobbying in Canada and other countries, and a growing body of research has documented both that extensive influence and the need for policy makers to be aware of it when creating policy that promotes the health and safety of all citizens.

Health Canada met with industry 56 per cent of the time regarding the 2016 Healthy Eating Strategy, researchers at the University of Ottawa found last year. And during creation of the recent Food Guide, Health Canada restricted industry lobbying — so effectively that industry persuaded officials at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada to lobby Health Canada on their behalf, as The Globe and Mail and other organizations reported.

Mulligan says the disparity in interactions with government among stakeholders was even greater for S-228, and that it marks a stark contrast between this bill and interactions on the Healthy Eating Strategy more broadly.

Industry lobbying has also been prominent on a stalled bill to introduce front-of-package labelling that would inform consumers about foods high in salt, sugar and saturated fat, said L’Abbé, who advised Health Canada on both bills and the Healthy Eating Strategy.

L’Abbé said that more transparency on interactions with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and other federal departments would help, as would more detail in the Registry of Lobbyists. All stakeholder comments related to proposed regulations are part of a public docket in the U.S., and some groups have called for a similar approach in Canada.

“We desperately need better management of the consultative process on legislative bills, for public health policy in the public good,” said L’Abbé.

This research was funded by the Joannah & Brian Lawson Centre for Child Nutrition and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.