Mobile Menu

- About Us

- Research

- Education

- Policy & Data

- News

- Resources

- Giving

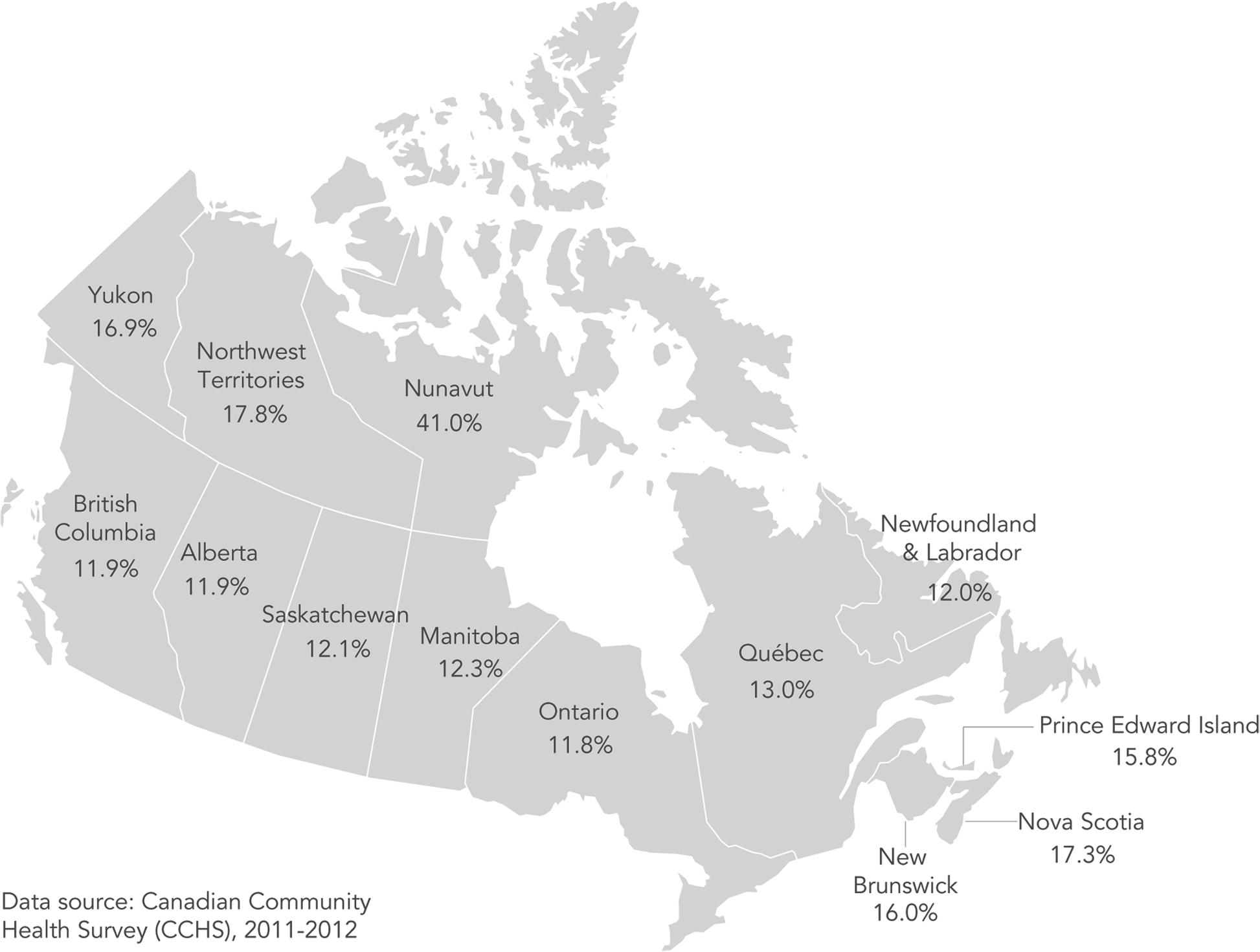

Canadian households that rely on publicly funded income supports are much more likely to face food insecurity than those reliant on employment income, according to new research from the University of Toronto. The study is one of the most comprehensive to elucidate the socio-demographics of food insecurity in Canada, and it shows wide disparities in risk by province and territory, age and Indigeneity, among other factors.

Food insecurity is the inadequate or uncertain access to food due to financial constraint, and a growing body of evidence shows it has major effects on physical and mental health, and health care costs.

Income supports associated with a high risk of food insecurity included social assistance, employment insurance and workers’ compensation, the researchers found — even after controlling for education, household composition and many other factors. Households reliant on social assistance were almost three times more likely to be food-insecure, and 16 times more likely when the researchers did not control for other factors.

“This study shows loud and clear that if you happen to be unfortunate enough to require income support, your probability of food insecurity is quite high, unless you’re a senior,” said Valerie Tarasuk, a professor of Nutritional Sciences at U of T and principal investigator on the study. “It really calls into question the adequacy of the income supports provided by Canada’s hallmark social programs, while highlighting the protective effect of public pensions for seniors.”

The research was published in the journal BMC Public Health earlier this month, and included data from 2011-12 on 120,000 households.

The study is the first to examine food insecurity by location of residence while accounting for a wide range of demographics, and it offers new insights on comparative risk among provinces and territories. Living in Nova Scotia or Alberta was associated with higher odds of marginal, moderate and severe food insecurity compared to Ontario, for example. And in Nunavut, the risk for severe food insecurity was more than six times higher than in Ontario.

Another novel finding was that households in Quebec had a lower risk of food insecurity than those in Ontario, despite a higher prevalence of the problem. “We only see the protection associated Quebec when we take into account socio-demographic differences of households in Quebec versus Ontario,” said Tarasuk, who is also a member of the Joannah & Brian Lawson Centre for Child Nutrition and the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at U of T. “If Quebec didn’t confer such protection on its residents, its prevalence would be way higher, given the population demographics.”

Tarasuk said the evidence does not show why living in Quebec limits risk for food insecurity, but that it raises questions about the province’s lower cost of living and household debt-to-asset ratio, its child care program and other social and family supports, and higher rates of unionization, which all warrant more study. Quebecers’ risk for severe food insecurity in particular was much lower — 41 per cent less than for Ontarians.

Households with Indigenous respondents were more likely to be food insecure than non-Indigenous Canadians, as other studies have found. But the researchers showed that even after controlling for other demographics, households with Indigenous respondents still had a 54 per cent higher risk. “Our study excludes people living on reserve, and so by design it doesn’t capture the worst of this problem,” said Tarasuk. “Yet these numbers are still picking up a bad story.”

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.